DNA, the fundamental molecule of life, serves as the instruction manual for building proteins. These proteins are the workhorses of the cell, carrying out countless functions. The bridge between DNA and proteins lies in the genetic code, expressed in units called codons.

The Language of Codons

Triplet Code

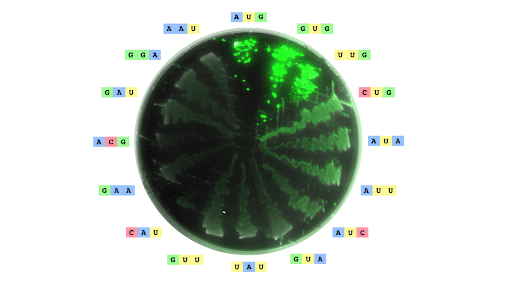

The building blocks of DNA are four nucleotides: adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G). These bases are arranged in sequences, and every three consecutive bases form a codon.

Genetic Dictionary

This correspondence is remarkably consistent across almost all living organisms, highlighting the universality of the genetic code.

Start and Stop Signals: The genetic code also includes start and stop codons. The start codon signals the beginning of a protein sequence, while stop codons mark its end.

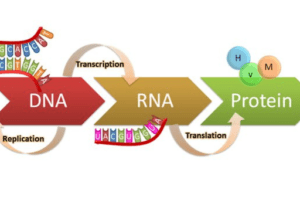

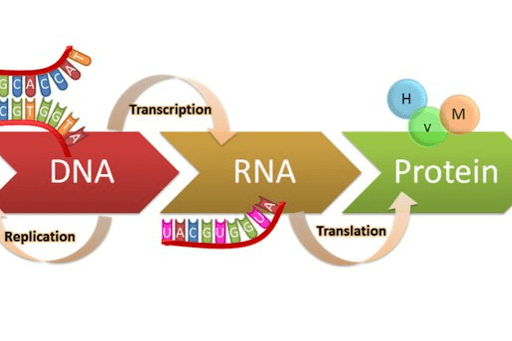

From DNA to Protein: The Central Dogma

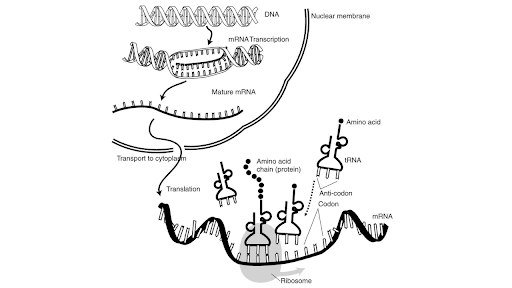

The process of converting DNA information into proteins involves two primary steps:

- Transcription:

-

-

- DNA unzips to expose the gene sequence.

- An enzyme called RNA polymerase creates a complementary RNA molecule, known as messenger RNA (mRNA), using the DNA as a template.

-

- Translation:

-

- The mRNA attaches to ribosomes, cellular structures responsible for protein synthesis.

- Transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules, each carrying a specific amino acid, recognize and bind to complementary codons on the mRNA.

- As the ribosome moves along the mRNA, amino acids are linked together, forming a polypeptide chain.

- This chain folds into a specific three-dimensional structure to become a functional protein.

The Impact of Codons

The precise sequence of codons in a DNA gene determines the exact order of amino acids in the resulting protein. This amino acid sequence is crucial because it dictates the protein’s structure and, ultimately, its function. Even a single change in a codon (a mutation) can have significant consequences, leading to altered protein function or disease.

DNA codons serve as the fundamental units of genetic information, providing the instructions for constructing the diverse array of proteins essential for life. The intricate processes of transcription and translation faithfully convert this coded information into the functional molecules that underpin all biological processes.

DNA, RNA, and Proteins: The Dynamic Trio

Imagine your body is a bustling factory that produces countless products. DNA is the factory’s master blueprint, containing all the instructions for making every product. It’s like a detailed recipe book, but one that covers everything from your eye color to your ability to digest food.

RNA is the factory’s copy machine. It takes a specific recipe (a gene) from the DNA blueprint and makes a copy. This copy, called messenger RNA (mRNA), is then sent out to the factory floor.

Proteins are the actual products of the factory. They’re like the skilled workers who follow the mRNA recipe to build the final product. Each protein has a specific job, from carrying oxygen in your blood to helping you digest your dinner.

So, to sum it up:

- DNA holds the complete set of instructions.

- RNA copies the instructions for a specific product.

- Proteins are products built based on those instructions.

This amazing teamwork between DNA, RNA, and proteins is what makes life possible!

What is the genetic code and how does it work?

Imagine the genetic code as a special language used by all living things. It’s like a secret code that tells cells how to build proteins.

Think of a protein as a long chain of beads. Each bead is an amino acid. The genetic code is a set of rules that determines which bead (amino acid) goes next in the chain. It’s like a recipe book for building proteins.

Here’s how it works:

Codons

Each “word” in this genetic recipe is called a codon. A codon is made up of three letters (these letters are actually chemical bases found in DNA).

Amino Acids

Each codon stands for a specific amino acid. So, when a cell reads the DNA recipe, it looks at the codons and matches them to the right amino acids.

Building the Protein

The cell links these amino acids together like beads on a string, following the order dictated by the codons.

It’s a complex process, but it’s incredibly precise. This genetic code is the reason why you have brown eyes, or why a bird can fly. It’s the blueprint for life!

How are codons translated into amino acids?

Imagine the DNA as a detailed recipe for building a protein. The recipe is written in a special language using three-letter “words” called codons. Each codon corresponds to a specific amino acid, which is like an ingredient in the recipe.

To translate this code, the cell uses a molecular machine called a ribosome. Think of it as a tiny factory worker. The ribosome reads the mRNA (a copy of the DNA recipe) three letters at a time.

For each codon, there’s a special delivery service: transfer RNA (tRNA). tRNA molecules are like tiny trucks that carry amino acids. Each tRNA has a specific code (anti-codon) that matches a particular codon.

When the ribosome reads a codon, the matching tRNA arrives with its amino acid cargo. The ribosome then links this amino acid to the growing protein chain. It’s like adding beads to a necklace, one bead at a time, following the exact order specified by the DNA recipe.

This process continues until the ribosome reaches a “stop” codon, signaling the end of the protein.

So, the journey from DNA code to protein involves a complex dance of molecules, all working together to translate the genetic message into the building blocks of life.

What is the process of protein synthesis?

Imagine building a complex model with thousands of tiny pieces. That’s essentially what a cell does when it makes a protein. This process is called protein synthesis.

It happens in two main steps:

Copying the Recipe

DNA blueprint The cell starts with a DNA molecule, which is like a detailed instruction manual.

Making a copy: A special enzyme called RNA polymerase reads the DNA and creates a copy called messenger RNA (mRNA). This is like photocopying a page from the recipe book.

Moving out: The mRNA leaves the nucleus and heads to the cell’s protein-building factories, the ribosomes.

Building the Protein

- Ribosome action: The ribosome is like a small machine that reads the mRNA code.

- Amino acid delivery: Transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules bring the correct amino acids to the ribosome based on the mRNA instructions. It’s like delivering the right ingredients to a baker.

- Chain reaction: The ribosome links these amino acids together, one by one, forming a long chain called a polypeptide.

- Finishing touches: This chain then folds into a specific shape to become a fully functional protein.

So, from the DNA blueprint to the finished protein product, it’s a complex dance of molecules working together to create the building blocks of life.

How do mutations in codons affect protein structure?

Each piece is crucial for the final picture. Now, imagine replacing one piece with the wrong one. It might not seem like a big deal, but it can completely change the final image. That’s kind of what happens when a mutation changes a codon in your DNA.

Codons are the building blocks of proteins. They’re like the instructions for assembling a protein. When a mutation changes a codon, it’s like changing a piece of the puzzle. This change can have big consequences for the final protein.

Wrong Piece, Wrong Place: Sometimes, a mutation changes a codon to one that codes for a different amino acid. This is like using the wrong puzzle piece. The protein might end up folded incorrectly, which can affect its job.

Stopping Short: Other times, a mutation can create a “stop” codon where there shouldn’t be one. This is like losing a piece of the puzzle. The protein gets cut short and might not work at all.

Shifting the Puzzle: Some mutations can shift the entire “reading frame” of the DNA, like adding or removing a piece from the puzzle. This messes up the whole sequence and usually creates a non-functional protein.

So, even a tiny change in the DNA code can have a big impact on the final protein product. This is why mutations can lead to everything from harmless variations to serious genetic disorders.

How do different codons code for the same amino acid?

The genetic code, a set of rules that translates nucleotide sequences into amino acid sequences, is a remarkable feat of biological engineering. It’s not just about creating proteins; it’s about creating an astonishing diversity of proteins that drive the complexity of life.

The Foundation of Diversity: Codons and Amino Acids

At its core, the genetic code is a system of triplets called codons. Each codon specifies a particular amino acid, or in some cases, signals the start or stop of protein synthesis. While there are only 20 standard amino acids, the combinations of four nucleotides (A, T, C, and G) allow for 64 different codons. This redundancy means multiple codons can code for the same amino acid, offering a degree of flexibility.

Building Complexity: Gene Length and Order

The length of a gene, the number of codons it contains, directly impacts the length of the resulting protein. A short gene will produce a smaller protein, while a long gene will result in a larger one. Moreover, the specific order of these codons is crucial. A change in even one codon can dramatically alter the amino acid sequence, leading to a completely different protein with a distinct function.

The Role of Alternative Splicing

Beyond the basic coding sequence, another layer of complexity arises from alternative splicing. Many genes can produce multiple protein variants through different combinations of exons (coding regions) and introns (non-coding regions). This process expands the protein repertoire without increasing the number of genes.

The Impact of Mutations

Mutations, changes in the DNA sequence, can introduce new variations. While many mutations are harmful, some can lead to beneficial changes. These changes can create proteins with novel functions, driving evolutionary adaptation.

The Unseen Orchestra: Protein Interactions

Proteins rarely function in isolation. They interact with other proteins, DNA, RNA, and small molecules to carry out their roles.

These interactions are influenced by protein structure, which is determined by the amino acid sequence. Even slight changes in amino acid sequence can alter protein interactions, leading to new functions and cellular behaviors.

In conclusion, the genetic code, combined with factors like gene length, alternative splicing, mutations, and protein interactions, creates an almost infinite potential for protein diversity. This diversity is the foundation for the incredible range of organisms and their complex biological processes found on Earth.